C - Language Overview

C is a general purpose high level language that was originally developed by Dennis M. Ritchie to develop the Unix operating system at Bell Labs. C was originally first implemented on the DEC PDP-11 computer in 1972.

In 1978, Brian Kernighan and Dennis Ritchie produced the first publicly available description of C, now known as the K&R standard.

The UNIX operating system, the C compiler, and essentially all UNIX applications programs have been written in C. The C has now become a widely used professional language for various reasons.

- Easy to learn

- Structured language

- It produces efficient programs.

- It can handle low-level activities.

- It can be compiled on a variety of computer platforms.

Facts about C

- C was invented to write an operating system called UNIX.

- C is a successor of B language which was introduced around 1970

- The language was formalized in 1988 by the American National Standard Institute (ANSI).

- The UNIX OS was totally written in C By 1973.

- Today C is the most widely used and popular System Programming Language.

- Most of the state of the art software's have been implemented using C.

- Today's most popular Linux OS and RBDMS MySQL have been written in C.

Why to use C ?

C was initially used for system development work, in particular the programs that make-up the operating system. C was adopted as a system development language because it produces code that runs nearly as fast as code written in assembly language. Some examples of the use of C might be:

- Operating Systems

- Language Compilers

- Assemblers

- Text Editors

- Print Spoolers

- Network Drivers

- Modern Programs

- Data Bases

- Language Interpreters

- Utilities

C Programs

A C program can vary from 3 lines to millions of lines and it should be written into one or more text files with extension ".c" for example hello.c. You can use "vi", "vim" or any other text editor to write your C program into a file.

This tutorial assumes that you know how to edit a text file and how to write source code inside a program file.

C - Environment Setup

Before you start doing programming using C programming language, you need following two software's available on your computer, (a) Text Editor and (b) The C Compiler.

Text Editor

This will be used to type your program. Examples of few editors include Windows Notepad, OS Edit command, Brief, Epsilon, EMACS, and vim or vi

Name and version of text editor can vary on different operating systems. For example Notepad will be used on Windows and vim or vi can be used on windows as well as Linux, or Unix.

The files you create with your editor are called source files and contain program source code. The source files for C programs are typically named with the extension .c.

Before starting your programming, make sure you have one text editor in place and you have enough experience to write a computer program, save it in a file, compile it and finally execute it.

The C Compiler

The source code written in source file is the human readable source for your program. It needs to be "compiled", to turn into machine language so that your CPU can actually execute the program as per instructions given.

This C programming language compiler will be used to compile your source code into final executable program. I assume you have basic knowledge about a programming language compiler.

Most frequently used and free available compiler is GNU C/C++ compiler, otherwise you can have compilers either from HP or Solaris if you have respective Operating Systems.

Following section guides you on how to install GNU C/C++ compiler on various OS. I'm mentioning C/C++ together because GNU gcc compiler works for both C and C++ programming languages.

Installation on Unix/Linux

If you are using Linux or Unix then check whether GCC is installed on your system by entering the following command from the command line:

$ gcc -v

If you have GNU compiler installed on your machine then it should print a message something as follows:

Using built-in specs. Target: i386-redhat-linux Configured with: ../configure --prefix=/usr ....... Thread model: posix gcc version 4.1.2 20080704 (Red Hat 4.1.2-46)

If GCC is not installed, then you will have to install it yourself using the detailed instructions available athttp://gcc.gnu.org/install/

This tutorial has been written based on Linux and all the given examples have been compiled on Cent OS flavor of Linux system.

Installation on Mac OS

If you use Mac OS X, the easiest way to obtain GCC is to download the Xcode development environment from Apple's web site and follow the simple installation instructions. Once you have Xcode setup, you will be able to use GNU compiler for C/C++.

Xcode is currently available at developer.apple.com/technologies/tools/.

Installation on Windows

To install GCC at Windows you need to install MinGW. To install MinGW, go to the MinGW homepage,www.mingw.org, and follow the link to the MinGW download page. Download the latest version of the MinGW installation program, which should be named MinGW-<version>.exe.

While installing MinWG, at a minimum, you must install gcc-core, gcc-g++, binutils, and the MinGW runtime, but you may wish to install more.

Add the bin subdirectory of your MinGW installation to your PATH environment variable so that you can specify these tools on the command line by their simple names.

When the installation is complete, you will be able to run gcc, g++, ar, ranlib, dlltool, and several other GNU tools from the Windows command line.

C - Program Structure

Before we study basic building blocks of the C programming language, let us look a bare minimum C program structure so that we can take it as a reference in upcoming chapters.

C Hello World Example

A C program basically consists of the following parts:

- Preprocessor Commands

- Functions

- Variables

- Statements & Expressions

- Comments

Let us look at a simple code that would print the words "Hello World":

#include <stdio.h> int main() { /* my first program in C */ printf("Hello, World! \n"); return 0; }

Let us look various parts of the above program:

- The first line of the program #include <stdio.h> is a preprocessor command which tells a C compiler to include stdio.h file before going to actual compilation.

- The next line int main() is the main function where program execution begins.

- The next line /*...*/ will be ignored by the compiler and it has been put to add additional comments in the program. So such lines are called comments in the program.

- The next line printf(...) is another function available in C which causes the message "Hello, World!" to be displayed on the screen.

- The next line return 0; terminates main()function and returns the value 0.

Compile & Execute C Program:

Lets look at how to save the source code in a file, and how to compile and run it. Following are the simple steps:

- Open a text editor and add the above mentioned code.

- Save the file as hello.c

- Open a command prompt and go to the directory where you saved the file.

- Type gcc hello.c and press enter to compile your code.

- If there are no errors in your code the command prompt will take you to the next line and would generate a.out executable file.

- Now type a.out to execute your program.

- You will be able to see "Hello World" printed on the screen

$ gcc hello.c $ ./a.out Hello, World!

Make sure that gcc compiler is in your path and that you are running it in the directory containing source file hello.c.

C - Basic Syntax

You have seen a basic structure of C program, so it will be easy to understand other basic building blocks of the C programming language.

Tokens in C

A C program consists of various tokens and a token is either a keyword, an identifier, a constant, a string literal, or a symbol. For example, the following C statement consists of five tokens:

printf("Hello, World! \n");

The individual tokens are:

printf ( "Hello, World! \n" ) ;

Semicolons ;

In C program, the semicolon is a statement terminator. That is, each individual statement must be ended with a semicolon. It indicates the end of one logical entity.

For example, following are two different statements:

printf("Hello, World! \n"); return 0;

Comments

Comments are like helping text in your C program and they are ignored by the compiler. They start with /* and terminates with the characters */ as shown below:

/* my first program in C */

You can not have comments with in comments and they do not occur within a string or character literals.

Identifiers

A C identifier is a name used to identify a variable, function, or any other user-defined item. An identifier starts with a letter A to Z or a to z or an underscore _ followed by zero or more letters, underscores, and digits (0 to 9).

C does not allow punctuation characters such as @, $, and % within identifiers. C is a case sensitive programming language. Thus Manpower and manpower are two different identifiers in C. Here are some examples of acceptable identifiers:

mohd zara abc move_name a_123

myname50 _temp j a23b9 retVal

Keywords

The following list shows the reserved words in C. These reserved words may not be used as constant or variable or any other identifier names.

| auto | else | long | switch |

| break | enum | register | typedef |

| case | extern | return | union |

| char | float | short | unsigned |

| const | for | signed | void |

| continue | goto | sizeof | volatile |

| default | if | static | while |

| do | int | struct | _Packed |

| double |

Whitespace in C

A line containing only whitespace, possibly with a comment, is known as a blank line, and a C compiler totally ignores it.

Whitespace is the term used in C to describe blanks, tabs, newline characters and comments. Whitespace separates one part of a statement from another and enables the compiler to identify where one element in a statement, such as int, ends and the next element begins. Therefore, in the following statement:

int age;

There must be at least one whitespace character (usually a space) between int and age for the compiler to be able to distinguish them. On the other hand, in the following statement

fruit = apples + oranges; // get the total fruit

No whitespace characters are necessary between fruit and =, or between = and apples, although you are free to include some if you wish for readability purpose.

C - Data Types

In the C programming language, data types refers to an extensive system used for declaring variables or functions of different types. The type of a variable determines how much space it occupies in storage and how the bit pattern stored is interpreted.

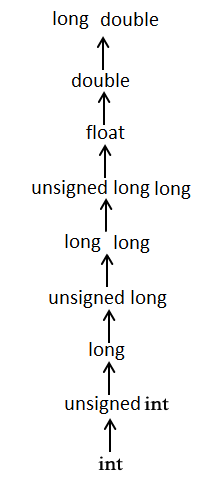

The types in C can be classified as follows:

| S.N. | Types and Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Basic Types: They are arithmetic types and consists of the two types: (a) integer types and (b) floating-point types. |

| 2 | Enumerated types: They are again arithmetic types and they are used to define variables that can only be assigned certain discrete integer values throughout the program. |

| 3 | The type void: The type specifier void indicates that no value is available. |

| 4 | Derived types: They include (a) Pointer types, (b) Array types, (c) Structure types, (d) Union types and (e) Function types. |

The array types and structure types are referred to collectively as the aggregate types. The type of a function specifies the type of the function's return value. We will see basic types in the following section where as other types will be covered in the upcoming chapters.

Integer Types

Following table gives you detail about standard integer types with its storage sizes and value ranges:

| Type | Storage size | Value range |

|---|---|---|

| char | 1 byte | -128 to 127 or 0 to 255 |

| unsigned char | 1 byte | 0 to 255 |

| signed char | 1 byte | -128 to 127 |

| int | 2 or 4 bytes | -32,768 to 32,767 or -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647 |

| unsigned int | 2 or 4 bytes | 0 to 65,535 or 0 to 4,294,967,295 |

| short | 2 bytes | -32,768 to 32,767 |

| unsigned short | 2 bytes | 0 to 65,535 |

| long | 4 bytes | -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647 |

| unsigned long | 4 bytes | 0 to 4,294,967,295 |

To get the exact size of a type or a variable on a particular platform, you can use the sizeof operator. The expressions sizeof(type) yields the storage size of the object or type in bytes. Following is an example to get the size of int type on any machine:

#include <stdio.h> #include <limits.h> int main() { printf("Storage size for int : %d \n", sizeof(int)); return 0; }

When you compile and execute the above program it produces following result on Linux:

Storage size for int : 4

Floating-Point Types

Following table gives you detail about standard float-point types with storage sizes and value ranges and their precision:

| Type | Storage size | Value range | Precision |

|---|---|---|---|

| float | 4 byte | 1.2E-38 to 3.4E+38 | 6 decimal places |

| double | 8 byte | 2.3E-308 to 1.7E+308 | 15 decimal places |

| long double | 10 byte | 3.4E-4932 to 1.1E+4932 | 19 decimal places |

The header file float.h defines macros that allow you to use these values and other details about the binary representation of real numbers in your programs. Following example will print storage space taken by a float type and its range values:

#include <stdio.h> #include <float.h> int main() { printf("Storage size for float : %d \n", sizeof(float)); printf("Minimum float positive value: %E\n", FLT_MIN ); printf("Maximum float positive value: %E\n", FLT_MAX ); printf("Precision value: %d\n", FLT_DIG ); return 0; }

When you compile and execute the above program it produces following result on Linux:

Storage size for float : 4 Minimum float positive value: 1.175494E-38 Maximum float positive value: 3.402823E+38 Precision value: 6

The void Type

The void type specifies that no value is available. It is used in three kinds of situations:

| S.N. | Types and Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Function returns as void There are various functions in C who do not return value or you can say they return void. A function with no return value has the return type as void. For example void exit (int status); |

| 2 | Function arguments as void There are various functions in C who do not accept any parameter. A function with no parameter can accept as a void. For example int rand(void); |

| 3 | Pointers to void A pointer of type void * represents the address of an object, but not its type. For example a memory allocation function void *malloc( size_t size ); returns a pointer to void which can be casted to any data type. |

The void type may not be understood to you at this point, so let us proceed and we will cover these concepts in upcoming chapters.

C - Variables

A variable is nothing but a name given to a storage area that our programs can manipulate. Each variable in C has a specific type, which determines the size and layout of the variable's memory; the range of values that can be stored within that memory; and the set of operations that can be applied to the variable.

The name of a variable can be composed of letters, digits, and the underscore character. It must begin with either a letter or an underscore. Upper and lowercase letters are distinct because C is case-sensitive. Based on the basic types explained in previous chapter, there will be following basic variable types:

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| char | Typically a single octet(one byte). This is an integer type. |

| int | The most natural size of integer for the machine. |

| float | A single-precision floating point value. |

| double | A double-precision floating point value. |

| void | Represents the absence of type. |

C programming language also allows to define various other type of variables which we will cover in subsequent chapters like Enumeration, Pointer, Array, Structure, Union etc. For this chapter, let us study only basic variable types.

Variable Declaration in C

All variables must be declared before we use them in C program, although certain declarations can be made implicitly by content. A declaration specifies a type, and contains a list of one or more variables of that type as follows:

type variable_list;

Here, type must be a valid C data type including char, int, float, double, or any user defined data type etc., and variable_list may consist of one or more identifier names separated by commas. Some valid variable declarations along with their definition are shown here:

int i, j, k; char c, ch; float f, salary; double d;

You can initialize a variable at the time of declaration as follows:

int i = 100;

An extern declaration is not a definition and does not allocate storage. In effect, it claims that a definition of the variable exists some where else in the program. A variable can be declared multiple times in a program, but it must be defined only once. Following is the declaration of a variable with extern keyword:

extern int i;

Though you can declare a variable multiple times in C program but it can be declared only once in a file, a function or a block of code.

Variable Initialization in C

Variables are initialized (assigned an value) with an equal sign followed by a constant expression. The general form of initialization is:

variable_name = value;

Variables can be initialized (assigned an initial value) in their declaration. The initializer consists of an equal sign followed by a constant expression as follows:

type variable_name = value;

Some examples are:

int d = 3, f = 5; /* initializing d and f. */ byte z = 22; /* initializes z. */ double pi = 3.14159; /* declares an approximation of pi. */ char x = 'x'; /* the variable x has the value 'x'. */

It is a good programming practice to initialize variables properly otherwise, sometime program would produce unexpected result. Try following example which makes use of various types of variables:

#include <stdio.h> int main () { /* variable declaration: */ int a, b; int c; float f; /* actual initialization */ a = 10; b = 20; c = a + b; printf("value of c : %d \n", c); f = 70.0/3.0; printf("value of f : %f \n", f); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

value of c : 30 value of f : 23.333334

Lvalues and Rvalues in C:

There are two kinds of expressions in C:

- lvalue : An expression that is an lvalue may appear as either the left-hand or right-hand side of an assignment.

- rvalue : An expression that is an rvalue may appear on the right- but not left-hand side of an assignment.

Variables are lvalues and so may appear on the left-hand side of an assignment. Numeric literals are rvalues and so may not be assigned and can not appear on the left-hand side. Following is a valid statement:

int g = 20;

But following is not a valid statement and would generate compile-time error:

10 = 20;

C - Constants and Literals

The constants refer to fixed values that the program may not alter during its execution. These fixed values are also called literals.

Constants can be of any of the basic data types like an integer constant, a floating constant, a character constant, or a string literal. There are also enumeration constants as well.

The constants are treated just like regular variables except that their values cannot be modified after their definition.

Integer literals

An integer literal can be a decimal, octal, or hexadecimal constant. A prefix specifies the base or radix: 0x or 0X for hexadecimal, 0 for octal, and nothing for decimal.

An integer literal can also have a suffix that is a combination of U and L, for unsigned and long, respectively. The suffix can be uppercase or lowercase and can be in any order.

Here are some examples of integer literals:

212 /* Legal */ 215u /* Legal */ 0xFeeL /* Legal */ 078 /* Illegal: 8 is not an octal digit */ 032UU /* Illegal: cannot repeat a suffix */

Following are other examples of various type of Integer literals:

85 /* decimal */ 0213 /* octal */ 0x4b /* hexadecimal */ 30 /* int */ 30u /* unsigned int */ 30l /* long */ 30ul /* unsigned long */

Floating-point literals

A floating-point literal has an integer part, a decimal point, a fractional part, and an exponent part. You can represent floating point literals either in decimal form or exponential form.

While representing using decimal form, you must include the decimal point, the exponent, or both and while representing using exponential form, you must include the integer part, the fractional part, or both. The signed exponent is introduced by e or E.

Here are some examples of floating-point literals:

3.14159 /* Legal */ 314159E-5L /* Legal */ 510E /* Illegal: incomplete exponent */ 210f /* Illegal: no decimal or exponent */ .e55 /* Illegal: missing integer or fraction */

Character constants

Character literals are enclosed in single quotes e.g., 'x' and can be stored in a simple variable of chartype.

A character literal can be a plain character (e.g., 'x'), an escape sequence (e.g., '\t'), or a universal character (e.g., '\u02C0').

There are certain characters in C when they are proceeded by a back slash they will have special meaning and they are used to represent like newline (\n) or tab (\t). Here you have a list of some of such escape sequence codes:

| Escape sequence | Meaning |

|---|---|

| \\ | \ character |

| \' | ' character |

| \" | " character |

| \? | ? character |

| \a | Alert or bell |

| \b | Backspace |

| \f | Form feed |

| \n | Newline |

| \r | Carriage return |

| \t | Horizontal tab |

| \v | Vertical tab |

| \ooo | Octal number of one to three digits |

| \xhh . . . | Hexadecimal number of one or more digits |

Following is the example to show few escape sequence characters:

#include <stdio.h> int main() { printf("Hello\tWorld\n\n"); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

Hello World

String literals

String literals or constants are enclosed in double quotes "". A string contains characters that are similar to character literals: plain characters, escape sequences, and universal characters.

You can break a long lines into multiple lines using string literals and separating them using whitespaces.

Here are some examples of string literals. All the three forms are identical strings.

"hello, dear" "hello, \ dear" "hello, " "d" "ear"

Defining Constants

There are two simple ways in C to define constants:

- Using #define preprocessor.

- Using const keyword.

The #define Preprocessor

Following is the form to use #define preprocessor to define a constant:

#define identifier value

Following example explains it in detail:

#include <stdio.h> #define LENGTH 10 #define WIDTH 5 #define NEWLINE '\n' int main() { int area; area = LENGTH * WIDTH; printf("value of area : %d", area); printf("%c", NEWLINE); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

value of area : 50

The const Keyword

You can use const prefix to declare constants with a specific type as follows:

const type variable = value;

Following example explains it in detail:

#include <stdio.h> int main() { const int LENGTH = 10; const int WIDTH = 5; const char NEWLINE = '\n'; int area; area = LENGTH * WIDTH; printf("value of area : %d", area); printf("%c", NEWLINE); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

value of area : 50

Note that it is a good programming practice to define constants in CAPITALS.

C - Storage Classes

A storage class defines the scope (visibility) and life time of variables and/or functions within a C Program. These specifiers precede the type that they modify. There are following storage classes which can be used in a C Program

- auto

- register

- static

- extern

The auto Storage Class

The auto storage class is the default storage class for all local variables.

{ int mount; auto int month; }

The example above defines two variables with the same storage class, auto can only be used within functions, i.e. local variables.

The register Storage Class

The register storage class is used to define local variables that should be stored in a register instead of RAM. This means that the variable has a maximum size equal to the register size (usually one word) and can't have the unary '&' operator applied to it (as it does not have a memory location).

{ register int miles; }

The register should only be used for variables that require quick access such as counters. It should also be noted that defining 'register' goes not mean that the variable will be stored in a register. It means that it MIGHT be stored in a register depending on hardware and implementation restrictions.

The static Storage Class

The static storage class instructs the compiler to keep a local variable in existence during the lifetime of the program instead of creating and destroying it each time it comes into and goes out of scope. Therefore, making local variables static allows them to maintain their values between function calls.

The static modifier may also be applied to global variables. When this is done, it causes that variable's scope to be restricted to the file in which it is declared.

In C programming, when static is used on a class data member, it causes only one copy of that member to be shared by all objects of its class.

#include <stdio.h> /* function declaration */ void func(void); static int count = 5; /* global variable */ main() { while(count--) { func(); } return 0; } /* function definition */ void func( void ) { static int i = 5; /* local static variable */ i++; printf("i is %d and count is %d\n", i, count); }

You may not understand this example at this time because I have used function and global variableswhich I have not explained so far. So for now let us proceed even if you do not understand it completely. When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

i is 6 and count is 4 i is 7 and count is 3 i is 8 and count is 2 i is 9 and count is 1 i is 10 and count is 0

The extern Storage Class

The extern storage class is used to give a reference of a global variable that is visible to ALL the program files. When you use 'extern' the variable cannot be initialized as all it does is point the variable name at a storage location that has been previously defined.

When you have multiple files and you define a global variable or function which will be used in other files also, then extern will be used in another file to give reference of defined variable or function. Just for understanding extern is used to declare a global variable or function in another files.

The extern modifier is most commonly used when there are two or more files sharing the same global variables or functions as explained below.

First File: main.c

#include <stdio.h> int count ; extern void write_extern(); main() { count = 5; write_extern(); }

Second File: write.c

#include <stdio.h> extern int count; void write_extern(void) { printf("count is %d\n", count); }

Here extern keyword is being used to declare count in the second file where as it has its definition in the first file main.c. Now compile these two files as follows:

$gcc main.c write.c

This will produce a.out executable program, when this program is executed, it produces following result:

5

C - Operators

An operator is a symbol that tells the compiler to perform specific mathematical or logical manipulations. C language is rich in built-in operators and provides following type of operators:

- Arithmetic Operators

- Relational Operators

- Logical Operators

- Bitwise Operators

- Assignment Operators

- Misc Operators

This tutorial will explain the arithmetic, relational, and logical, bitwise, assignment and other operators one by one.

Arithmetic Operators

Following table shows all the arithmetic operators supported by C language. Assume variable A holds 10 and variable B holds 20 then:

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| + | Adds two operands | A + B will give 30 |

| - | Subtracts second operand from the first | A - B will give -10 |

| * | Multiply both operands | A * B will give 200 |

| / | Divide numerator by de-numerator | B / A will give 2 |

| % | Modulus Operator and remainder of after an integer division | B % A will give 0 |

| ++ | Increment operator increases integer value by one | A++ will give 11 |

| -- | Decrement operator decreases integer value by one | A-- will give 9 |

Relational Operators

Following table shows all the relational operators supported by C language. Assume variable A holds 10 and variable B holds 20 then:

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| == | Checks if the value of two operands is equal or not, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A == B) is not true. |

| != | Checks if the value of two operands is equal or not, if values are not equal then condition becomes true. | (A != B) is true. |

| > | Checks if the value of left operand is greater than the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A > B) is not true. |

| < | Checks if the value of left operand is less than the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A < B) is true. |

| >= | Checks if the value of left operand is greater than or equal to the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A >= B) is not true. |

| <= | Checks if the value of left operand is less than or equal to the value of right operand, if yes then condition becomes true. | (A <= B) is true. |

Logical Operators

Following table shows all the logical operators supported by C language. Assume variable A holds 1 and variable B holds 0 then:

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| && | Called Logical AND operator. If both the operands are non zero then condition becomes true. | (A && B) is false. |

| || | Called Logical OR Operator. If any of the two operands is non zero then condition becomes true. | (A || B) is true. |

| ! | Called Logical NOT Operator. Use to reverses the logical state of its operand. If a condition is true then Logical NOT operator will make false. | !(A && B) is true. |

Bitwise Operators

Bitwise operator works on bits and perform bit by bit operation. The truth tables for &, |, and ^ are as follows:

| p | q | p & q | p | q | p ^ q |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Assume if A = 60; and B = 13; Now in binary format they will be as follows:

A = 0011 1100

B = 0000 1101

-----------------

A&B = 0000 1100

A|B = 0011 1101

A^B = 0011 0001

~A = 1100 0011

The Bitwise operators supported by C language are listed in the following table. Assume variable A holds 60 and variable B holds 13 then:

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| & | Binary AND Operator copies a bit to the result if it exists in both operands. | (A & B) will give 12 which is 0000 1100 |

| | | Binary OR Operator copies a bit if it exists in either operand. | (A | B) will give 61 which is 0011 1101 |

| ^ | Binary XOR Operator copies the bit if it is set in one operand but not both. | (A ^ B) will give 49 which is 0011 0001 |

| ~ | Binary Ones Complement Operator is unary and has the effect of 'flipping' bits. | (~A ) will give -60 which is 1100 0011 |

| << | Binary Left Shift Operator. The left operands value is moved left by the number of bits specified by the right operand. | A << 2 will give 240 which is 1111 0000 |

| >> | Binary Right Shift Operator. The left operands value is moved right by the number of bits specified by the right operand. | A >> 2 will give 15 which is 0000 1111 |

Assignment Operators

There are following assignment operators supported by C language:

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| = | Simple assignment operator, Assigns values from right side operands to left side operand | C = A + B will assign value of A + B into C |

| += | Add AND assignment operator, It adds right operand to the left operand and assign the result to left operand | C += A is equivalent to C = C + A |

| -= | Subtract AND assignment operator, It subtracts right operand from the left operand and assign the result to left operand | C -= A is equivalent to C = C - A |

| *= | Multiply AND assignment operator, It multiplies right operand with the left operand and assign the result to left operand | C *= A is equivalent to C = C * A |

| /= | Divide AND assignment operator, It divides left operand with the right operand and assign the result to left operand | C /= A is equivalent to C = C / A |

| %= | Modulus AND assignment operator, It takes modulus using two operands and assign the result to left operand | C %= A is equivalent to C = C % A |

| <<= | Left shift AND assignment operator | C <<= 2 is same as C = C << 2 |

| >>= | Right shift AND assignment operator | C >>= 2 is same as C = C >> 2 |

| &= | Bitwise AND assignment operator | C &= 2 is same as C = C & 2 |

| ^= | bitwise exclusive OR and assignment operator | C ^= 2 is same as C = C ^ 2 |

| |= | bitwise inclusive OR and assignment operator | C |= 2 is same as C = C | 2 |

Misc Operators ↦ sizeof & ternary

There are few other important operators including sizeof and ? : supported by C Language.

Show Examples

| Operator | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| sizeof() | Returns the size of an variable. | sizeof(a), where a is integer, will return 4. |

| & | Returns the address of an variable. | &a; will give actual address of the variable. |

| * | Pointer to a variable. | *a; will pointer to a variable. |

| ? : | Conditional Expression | If Condition is true ? Then value X : Otherwise value Y |

Operators Precedence in C

Operator precedence determines the grouping of terms in an expression. This affects how an expression is evaluated. Certain operators have higher precedence than others; for example, the multiplication operator has higher precedence than the addition operator:

For example x = 7 + 3 * 2; Here x is assigned 13, not 20 because operator * has higher precedence than + so it first get multiplied with 3*2 and then adds into 7.

Here operators with the highest precedence appear at the top of the table, those with the lowest appear at the bottom. Within an expression, higher precedence operators will be evaluated first.

Show Examples

| Category | Operator | Associativity |

|---|---|---|

| Postfix | () [] -> . ++ - - | Left to right |

| Unary | + - ! ~ ++ - - (type)* & sizeof | Right to left |

| Multiplicative | * / % | Left to right |

| Additive | + - | Left to right |

| Shift | << >> | Left to right |

| Relational | < <= > >= | Left to right |

| Equality | == != | Left to right |

| Bitwise AND | & | Left to right |

| Bitwise XOR | ^ | Left to right |

| Bitwise OR | | | Left to right |

| Logical AND | && | Left to right |

| Logical OR | || | Left to right |

| Conditional | ?: | Right to left |

| Assignment | = += -= *= /= %=>>= <<= &= ^= |= | Right to left |

| Comma | , | Left to right |

C - Decision Making

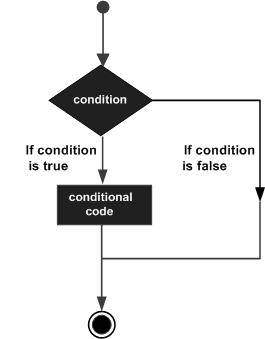

Decision making structures require that the programmer specify one or more conditions to be evaluated or tested by the program, along with a statement or statements to be executed if the condition is determined to be true, and optionally, other statements to be executed if the condition is determined to be false.

Following is the general from of a typical decision making structure found in most of the programming languages:

C programming language assumes any non-zero and non-null values as true and if it is either zero ornull then it is assumed as false value.

C programming language provides following types of decision making statements. Click the following links to check their detail.

| Statement | Description |

|---|---|

| if statement | An if statement consists of a boolean expression followed by one or more statements. |

| if...else statement | An if statement can be followed by an optional else statement, which executes when the boolean expression is false. |

| nested if statements | You can use one if or else if statement inside another if or else if statement(s). |

| switch statement | A switch statement allows a variable to be tested for equality against a list of values. |

| nested switch statements | You can use one swicth statement inside another switchstatement(s). |

The ? : Operator:

We have covered conditional operator ? : in previous chapter which can be used to replace if...elsestatements. It has the following general form:

Exp1 ? Exp2 : Exp3;

Where Exp1, Exp2, and Exp3 are expressions. Notice the use and placement of the colon.

The value of a ? expression is determined like this: Exp1 is evaluated. If it is true, then Exp2 is evaluated and becomes the value of the entire ? expression. If Exp1 is false, then Exp3 is evaluated and its value becomes the value of the expression.

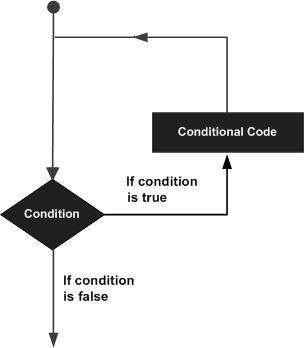

C - Loops

There may be a situation when you need to execute a block of code several number of times. In general statements are executed sequentially: The first statement in a function is executed first, followed by the second, and so on.

Programming languages provide various control structures that allow for more complicated execution paths.

A loop statement allows us to execute a statement or group of statements multiple times and following is the general from of a loop statement in most of the programming languages:

C programming language provides following types of loop to handle looping requirements. Click the following links to check their detail.

| Loop Type | Description |

|---|---|

| while loop | Repeats a statement or group of statements while a given condition is true. It tests the condition before executing the loop body. |

| for loop | Execute a sequence of statements multiple times and abbreviates the code that manages the loop variable. |

| do...while loop | Like a while statement, except that it tests the condition at the end of the loop body |

| nested loops | You can use one or more loop inside any another while, for or do..while loop. |

Loop Control Statements:

Loop control statements change execution from its normal sequence. When execution leaves a scope, all automatic objects that were created in that scope are destroyed.

C supports the following control statements. Click the following links to check their detail.

| Control Statement | Description |

|---|---|

| break statement | Terminates the loop or switch statement and transfers execution to the statement immediately following the loop or switch. |

| continue statement | Causes the loop to skip the remainder of its body and immediately retest its condition prior to reiterating. |

| goto statement | Transfers control to the labeled statement. Though it is not advised to use goto statement in your program. |

The Infinite Loop:

A loop becomes infinite loop if a condition never becomes false. The for loop is traditionally used for this purpose. Since none of the three expressions that form the for loop are required, you can make an endless loop by leaving the conditional expression empty.

#include <stdio.h> int main () { for( ; ; ) { printf("This loop will run forever.\n"); } return 0; }

When the conditional expression is absent, it is assumed to be true. You may have an initialization and increment expression, but C programmers more commonly use the for(;;) construct to signify an infinite loop.

NOTE: You can terminate an infinite loop by pressing Ctrl + C keys.

C - Functions

A function is a group of statements that together perform a task. Every C program has at least one function which is main(), and all the most trivial programs can define additional functions.

You can divide up your code into separate functions. How you divide up your code among different functions is up to you, but logically the division usually is so each function performs a specific task.

A function declaration tells the compiler about a function's name, return type, and parameters. A function definition provides the actual body of the function.

The C standard library provides numerous built-in functions that your program can call. For example, function strcat() to concatenate two strings, function memcpy() to copy one memory location to another location and many more functions.

A function is known with various names like a method or a sub-routine or a procedure etc.

Defining a Function:

The general form of a function definition in C programming language is as follows:

return_type function_name( parameter list ) { body of the function }

A function definition in C programming language consists of a function header and a function body. Here are all the parts of a function:

- Return Type: A function may return a value. The return_type is the data type of the value the function returns. Some functions perform the desired operations without returning a value. In this case, the return_type is the keyword void.

- Function Name: This is the actual name of the function. The function name and the parameter list together constitute the function signature.

- Parameters: A parameter is like a placeholder. When a function is invoked, you pass a value to the parameter. This value is referred to as actual parameter or argument. The parameter list refers to the type, order, and number of the parameters of a function. Parameters are optional; that is, a function may contain no parameters.

- Function Body: The function body contains a collection of statements that define what the function does.

Example:

Following is the source code for a function called max(). This function takes two parameters num1 and num2 and returns the maximum between the two:

/* function returning the max between two numbers */ int max(int num1, int num2) { /* local variable declaration */ int result; if (num1 > num2) result = num1; else result = num2; return result; }

Function Declarations:

A function declaration tells the compiler about a function name and how to call the function. The actual body of the function can be defined separately.

A function declaration has the following parts:

return_type function_name( parameter list );

For the above defined function max(), following is the function declaration:

int max(int num1, int num2);

Parameter names are not important in function declaration only their type is required, so following is also valid declaration:

int max(int, int);

Function declaration is required when you define a function in one source file and you call that function in another file. In such case you should declare the function at the top of the file calling the function.

Calling a Function:

While creating a C function, you give a definition of what the function has to do. To use a function, you will have to call that function to perform the defined task.

When a program calls a function, program control is transferred to the called function. A called function performs defined task and when its return statement is executed or when its function-ending closing brace is reached, it returns program control back to the main program.

To call a function you simply need to pass the required parameters along with function name and if function returns a value then you can store returned value. For example:

#include <stdio.h> /* function declaration */ int max(int num1, int num2); int main () { /* local variable definition */ int a = 100; int b = 200; int ret; /* calling a function to get max value */ ret = max(a, b); printf( "Max value is : %d\n", ret ); return 0; } /* function returning the max between two numbers */ int max(int num1, int num2) { /* local variable declaration */ int result; if (num1 > num2) result = num1; else result = num2; return result; }

I kept max() function along with main() function and complied the source code. While running final executable, it would produce following result:

Max value is : 200

Function Arguments:

If a function is to use arguments, it must declare variables that accept the values of the arguments. These variables are called the formal parameters of the function.

The formal parameters behave like other local variables inside the function and are created upon entry into the function and destroyed upon exit.

While calling a function, there are two ways that arguments can be passed to a function:

| Call Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Call by value | This method copies the actual value of an argument into the formal parameter of the function. In this case, changes made to the parameter inside the function have no effect on the argument. |

| Call by reference | This method copies the address of an argument into the formal parameter. Inside the function, the address is used to access the actual argument used in the call. This means that changes made to the parameter affect the argument. |

By default, C uses call by value to pass arguments. In general, this means that code within a function cannot alter the arguments used to call the function and above mentioned example while calling max() function used the same method.

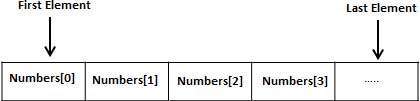

C - Arrays

C programming language provides a data structure called the array, which can store a fixed-size sequential collection of elements of the same type. An array is used to store a collection of data, but it is often more useful to think of an array as a collection of variables of the same type.

Instead of declaring individual variables, such as number0, number1, ..., and number99, you declare one array variable such as numbers and use numbers[0], numbers[1], and ..., numbers[99] to represent individual variables. A specific element in an array is accessed by an index.

All arrays consist of contiguous memory locations. The lowest address corresponds to the first element and the highest address to the last element.

Declaring Arrays

To declare an array in C, a programmer specifies the type of the elements and the number of elements required by an array as follows:

type arrayName [ arraySize ];

This is called a single-dimensional array. The arraySize must be an integer constant greater than zero and type can be any valid C data type. For example, to declare a 10-element array called balance of type double, use this statement:

double balance[10];

Now balance is avariable array which is sufficient to hold upto 10 double numbers.

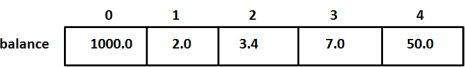

Initializing Arrays

You can initialize array in C either one by one or using a single statement as follows:

double balance[5] = {1000.0, 2.0, 3.4, 17.0, 50.0};

The number of values between braces { } can not be larger than the number of elements that we declare for the array between square brackets [ ]. Following is an example to assign a single element of the array:

If you omit the size of the array, an array just big enough to hold the initialization is created. Therefore, if you write:

double balance[] = {1000.0, 2.0, 3.4, 17.0, 50.0};

You will create exactly the same array as you did in the previous example.

balance[4] = 50.0;

The above statement assigns element number 5th in the array a value of 50.0. Array with 4th index will be 5th ie. last element because all arrays have 0 as the index of their first element which is also called base index. Following is the pictorial representation of the same array we discussed above:

Accessing Array Elements

An element is accessed by indexing the array name. This is done by placing the index of the element within square brackets after the name of the array. For example:

double salary = balance[9];

The above statement will take 10th element from the array and assign the value to salary variable. Following is an example which will use all the above mentioned three concepts viz. declaration, assignment and accessing arrays:

#include <stdio.h> int main () { int n[ 10 ]; /* n is an array of 10 integers */ int i,j; /* initialize elements of array n to 0 */ for ( i = 0; i < 10; i++ ) { n[ i ] = i + 100; /* set element at location i to i + 100 */ } /* output each array element's value */ for (j = 0; j < 10; j++ ) { printf("Element[%d] = %d\n", j, n[j] ); } return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

Element[0] = 100 Element[1] = 101 Element[2] = 102 Element[3] = 103 Element[4] = 104 Element[5] = 105 Element[6] = 106 Element[7] = 107 Element[8] = 108 Element[9] = 109

C Arrays in Detail

Arrays are important to C and should need lots of more detail. There are following few important concepts related to array which should be clear to a C programmer:

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| Multi-dimensional arrays | C supports multidimensional arrays. The simplest form of the multidimensional array is the two-dimensional array. |

| Passing arrays to functions | You can pass to the function a pointer to an array by specifying the array's name without an index. |

| Return array from a function | C allows a function to return an array. |

| Pointer to an array | You can generate a pointer to the first element of an array by simply specifying the array name, without any index. |

C - Pointers

Pointers in C are easy and fun to learn. Some C programming tasks are performed more easily with pointers, and other tasks, such as dynamic memory allocation, cannot be performed without using pointers. So it becomes necessary to learn pointers to become a perfect C programmer. Let's start learning them in simple and easy steps.

As you know every variable is a memory location and every memory location has its address defined which can be accessed using ampersand (&) operator which denotes an address in memory. Consider the following example which will print the address of the variables defined:

#include <stdio.h> int main () { int var1; char var2[10]; printf("Address of var1 variable: %x\n", &var1 ); printf("Address of var2 variable: %x\n", &var2 ); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces result something as follows:

Address of var1 variable: bff5a400 Address of var2 variable: bff5a3f6

So you understood what is memory address and how to access it, so base of the concept is over. Now let us see what is a pointer.

What Are Pointers?

A pointer is a variable whose value is the address of another variable ie. direct address of the memory location. Like any variable or constant, you must declare a pointer before you can use it to store any variable address. The general form of a pointer variable declaration is:

type *var-name;

Here, type is the pointer's base type; it must be a valid C data type and var-name is the name of the pointer variable. The asterisk * you used to declare a pointer is the same asterisk that you use for multiplication. However, in this statement the asterisk is being used to designate a variable as a pointer. Following are the valid pointer declaration:

int *ip; /* pointer to an integer */ double *dp; /* pointer to a double */ float *fp; /* pointer to a float */ char *ch /* pointer to a character */

The actual data type of the value of all pointers, whether integer, float, character, or otherwise, is the same, a long hexadecimal number that represents a memory address. The only difference between pointers of different data types is the data type of the variable or constant that the pointer points to.

How to use Pointers?

There are few important operations which we will do with the help of pointers very frequently. (a) we define a pointer variables (b) assign the address of a variable to a pointer and (c) finally access the value at the address available in the pointer variable. This is done by using unary operator * that returns the value of the variable located at the address specified by its operand. Following example makes use of these operations:

#include <stdio.h> int main () { int var = 20; /* actual variable declaration */ int *ip; /* pointer variable declaration */ ip = &var; /* store address of var in pointer variable*/ printf("Address of var variable: %x\n", &var ); /* address stored in pointer variable */ printf("Address stored in ip variable: %x\n", ip ); /* access the value using the pointer */ printf("Value of *ip variable: %d\n", *ip ); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces result something as follows:

Address of var variable: bffd8b3c Address stored in ip variable: bffd8b3c Value of *ip variable: 20

NULL Pointers in C

It is always a good practice to assign a NULL value to a pointer variable in case you do not have exact address to be assigned. This is done at the time of variable declaration. A pointer that is assigned NULL is called a null pointer.

The NULL pointer is a constant with a value of zero defined in several standard libraries. Consider the following program:

#include <stdio.h> int main () { int *ptr = NULL; printf("The value of ptr is : %x\n", ptr ); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

The value of ptr is 0

On most of the operating systems, programs are not permitted to access memory at address 0 because that memory is reserved by the operating system. However, the memory address 0 has special significance; it signals that the pointer is not intended to point to an accessible memory location. But by convention, if a pointer contains the null (zero) value, it is assumed to point to nothing.

To check for a null pointer you can use an if statement as follows:

if(ptr) /* succeeds if p is not null */ if(!ptr) /* succeeds if p is null */

C Pointers in Detail:

Pointers have many but easy concepts and they are very important to C programming. There are following few important pointer concepts which should be clear to a C programmer:

| Concept | Description |

|---|---|

| C - Pointer arithmetic | There are four arithmetic operators that can be used on pointers: ++, --, +, - |

| C - Array of pointers | You can define arrays to hold a number of pointers. |

| C - Pointer to pointer | C allows you to have pointer on a pointer and so on. |

| Passing pointers to functions in C | Passing an argument by reference or by address both enable the passed argument to be changed in the calling function by the called function. |

| Return pointer from functions in C | C allows a function to return a pointer to local variable, static variable and dynamically allocated memory as well. |

C - Strings

The string in C programming language is actually a one-dimensional array of characters which is terminated by a null character '\0'. Thus a null-terminated string contains the characters that comprise the string followed by a null.

The following declaration and initialization create a string consisting of the word "Hello". To hold the null character at the end of the array, the size of the character array containing the string is one more than the number of characters in the word "Hello."

char greeting[6] = {'H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', '\0'};

If you follow the rule of array initialization then you can write the above statement as follows:

char greeting[] = "Hello";

Following is the memory presentation of above defined string in C/C++:

Actually, you do not place the null character at the end of a string constant. The C compiler automatically places the '\0' at the end of the string when it initializes the array. Let us try to print above mentioned string:

#include <stdio.h> int main () { char greeting[6] = {'H', 'e', 'l', 'l', 'o', '\0'}; printf("Greeting message: %s\n", greeting ); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces result something as follows:

Greeting message: Hello

C supports a wide range of functions that manipulate null-terminated strings:

| S.N. | Function & Purpose |

|---|---|

| 1 | strcpy(s1, s2); Copies string s2 into string s1. |

| 2 | strcat(s1, s2); Concatenates string s2 onto the end of string s1. |

| 3 | strlen(s1); Returns the length of string s1. |

| 4 | strcmp(s1, s2); Returns 0 if s1 and s2 are the same; less than 0 if s1<s2; greater than 0 if s1>s2. |

| 5 | strchr(s1, ch); Returns a pointer to the first occurrence of character ch in string s1. |

| 6 | strstr(s1, s2); Returns a pointer to the first occurrence of string s2 in string s1. |

Following example makes use of few of the above mentioned functions:

#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> int main () { char str1[12] = "Hello"; char str2[12] = "World"; char str3[12]; int len ; /* copy str1 into str3 */ strcpy(str3, str1); printf("strcpy( str3, str1) : %s\n", str3 ); /* concatenates str1 and str2 */ strcat( str1, str2); printf("strcat( str1, str2): %s\n", str1 ); /* total lenghth of str1 after concatenation */ len = strlen(str1); printf("strlen(str1) : %d\n", len ); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces result something as follows:

strcpy( str3, str1) : Hello strcat( str1, str2): HelloWorld strlen(str1) : 10

You can find a complete list of c string related functions in C Standard Library.

C - Structures

C arrays allow you to define type of variables that can hold several data items of the same kind butstructure is another user defined data type available in C programming, which allows you to combine data items of different kinds.

Structures are used to represent a record, Suppose you want to keep track of your books in a library. You might want to track the following attributes about each book:

- Title

- Author

- Subject

- Book ID

Defining a Structure

To define a structure, you must use the struct statement. The struct statement defines a new data type, with more than one member for your program. The format of the struct statement is this:

struct [structure tag] { member definition; member definition; ... member definition; } [one or more structure variables];

The structure tag is optional and each member definition is a normal variable definition, such as int i; or float f; or any other valid variable definition. At the end of the structure's definition, before the final semicolon, you can specify one or more structure variables but it is optional. Here is the way you would declare the Book structure:

struct Books { char title[50]; char author[50]; char subject[100]; int book_id; } book;

Accessing Structure Members

To access any member of a structure, we use the member access operator (.). The member access operator is coded as a period between the structure variable name and the structure member that we wish to access. You would use struct keyword to define variables of structure type. Following is the example to explain usage of structure:

#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> struct Books { char title[50]; char author[50]; char subject[100]; int book_id; }; int main( ) { struct Books Book1; /* Declare Book1 of type Book */ struct Books Book2; /* Declare Book2 of type Book */ /* book 1 specification */ strcpy( Book1.title, "C Programming"); strcpy( Book1.author, "Nuha Ali"); strcpy( Book1.subject, "C Programming Tutorial"); Book1.book_id = 6495407; /* book 2 specification */ strcpy( Book2.title, "Telecom Billing"); strcpy( Book2.author, "Zara Ali"); strcpy( Book2.subject, "Telecom Billing Tutorial"); Book2.book_id = 6495700; /* print Book1 info */ printf( "Book 1 title : %s\n", Book1.title); printf( "Book 1 author : %s\n", Book1.author); printf( "Book 1 subject : %s\n", Book1.subject); printf( "Book 1 book_id : %d\n", Book1.book_id); /* print Book2 info */ printf( "Book 2 title : %s\n", Book2.title); printf( "Book 2 author : %s\n", Book2.author); printf( "Book 2 subject : %s\n", Book2.subject); printf( "Book 2 book_id : %d\n", Book2.book_id); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

Book 1 title : C Programming Book 1 author : Nuha Ali Book 1 subject : C Programming Tutorial Book 1 book_id : 6495407 Book 2 title : Telecom Billing Book 2 author : Zara Ali Book 2 subject : Telecom Billing Tutorial Book 2 book_id : 6495700

Structures as Function Arguments

You can pass a structure as a function argument in very similar way as you pass any other variable or pointer. You would access structure variables in the similar way as you have accessed in the above example:

#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> struct Books { char title[50]; char author[50]; char subject[100]; int book_id; }; /* function declaration */ void printBook( struct Books book ); int main( ) { struct Books Book1; /* Declare Book1 of type Book */ struct Books Book2; /* Declare Book2 of type Book */ /* book 1 specification */ strcpy( Book1.title, "C Programming"); strcpy( Book1.author, "Nuha Ali"); strcpy( Book1.subject, "C Programming Tutorial"); Book1.book_id = 6495407; /* book 2 specification */ strcpy( Book2.title, "Telecom Billing"); strcpy( Book2.author, "Zara Ali"); strcpy( Book2.subject, "Telecom Billing Tutorial"); Book2.book_id = 6495700; /* print Book1 info */ printBook( Book1 ); /* Print Book2 info */ printBook( Book2 ); return 0; } void printBook( struct Books book ) { printf( "Book title : %s\n", book.title); printf( "Book author : %s\n", book.author); printf( "Book subject : %s\n", book.subject); printf( "Book book_id : %d\n", book.book_id); }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

Book title : C Programming Book author : Nuha Ali Book subject : C Programming Tutorial Book book_id : 6495407 Book title : Telecom Billing Book author : Zara Ali Book subject : Telecom Billing Tutorial Book book_id : 6495700

Pointers to Structures

You can define pointers to structures in very similar way as you define pointer to any other variable as follows:

struct Books *struct_pointer;

Now you can store the address of a structure variable in the above defined pointer variable. To find the address of a structure variable, place the & operator before the structure's name as follows:

struct_pointer = &Book1;

To access the members of a structure using a pointer to that structure, you must use the -> operator as follows:

struct_pointer->title;

Let us re-write above example using structure pointer, hope this will be easy for you to understand the concept:

#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> struct Books { char title[50]; char author[50]; char subject[100]; int book_id; }; /* function declaration */ void printBook( struct Books *book ); int main( ) { struct Books Book1; /* Declare Book1 of type Book */ struct Books Book2; /* Declare Book2 of type Book */ /* book 1 specification */ strcpy( Book1.title, "C Programming"); strcpy( Book1.author, "Nuha Ali"); strcpy( Book1.subject, "C Programming Tutorial"); Book1.book_id = 6495407; /* book 2 specification */ strcpy( Book2.title, "Telecom Billing"); strcpy( Book2.author, "Zara Ali"); strcpy( Book2.subject, "Telecom Billing Tutorial"); Book2.book_id = 6495700; /* print Book1 info by passing address of Book1 */ printBook( &Book1 ); /* print Book2 info by passing address of Book2 */ printBook( &Book2 ); return 0; } void printBook( struct Books *book ) { printf( "Book title : %s\n", book->title); printf( "Book author : %s\n", book->author); printf( "Book subject : %s\n", book->subject); printf( "Book book_id : %d\n", book->book_id); }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

Book title : C Programming Book author : Nuha Ali Book subject : C Programming Tutorial Book book_id : 6495407 Book title : Telecom Billing Book author : Zara Ali Book subject : Telecom Billing Tutorial Book book_id : 6495700

Bit Fields

Bit Fields allow the packing of data in a structure. This is especially useful when memory or data storage is at a premium. Typical examples:

- Packing several objects into a machine word. e.g. 1 bit flags can be compacted.

- Reading external file formats -- non-standard file formats could be read in. E.g. 9 bit integers.

C allows us do this in a structure definition by putting :bit length after the variable.For example:

struct packed_struct { unsigned int f1:1; unsigned int f2:1; unsigned int f3:1; unsigned int f4:1; unsigned int type:4; unsigned int my_int:9; } pack;

Here the packed_struct contains 6 members: Four 1 bit flags f1..f3, a 4 bit type and a 9 bit my_int.

C automatically packs the above bit fields as compactly as possible, provided that the maximum length of the field is less than or equal to the integer word length of the computer. If this is not the case then some compilers may allow memory overlap for the fields whilst other would store the next field in the next word.

C - Unions

A union is a special data type available in C that enables you to store different data types in the same memory location. You can define a union with many members, but only one member can contain a value at any given time. Unions provide an efficient way of using the same memory location for multi-purpose.

Defining a Union

To define a union, you must use the union statement in very similar was as you did while defining structure. The union statement defines a new data type, with more than one member for your program. The format of the union statement is as follows:

union [union tag] { member definition; member definition; ... member definition; } [one or more union variables];

The union tag is optional and each member definition is a normal variable definition, such as int i; or float f; or any other valid variable definition. At the end of the union's definition, before the final semicolon, you can specify one or more union variables but it is optional. Here is the way you would define a union type named Data which has the three members i, f, and str:

union Data { int i; float f; char str[20]; } data;

Now a variable of Data type can store an integer, a floating-point number, or a string of characters. This means that a single variable ie. same memory location can be used to store multiple types of data. You can use any built-in or user defined data types inside a union based on your requirement.

The memory occupied by a union will be large enough to hold the largest member of the union. For example, in above example Data type will occupy 20 bytes of memory space because this is the maximum space which can be occupied by character string. Following is the example which will display total memory size occupied by the above union:

#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> union Data { int i; float f; char str[20]; }; int main( ) { union Data data; printf( "Memory size occupied by data : %d\n", sizeof(data)); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

Memory size occupied by data : 20

Accessing Union Members

To access any member of a union, we use the member access operator (.). The member access operator is coded as a period between the union variable name and the union member that we wish to access. You would use union keyword to define variables of union type. Following is the example to explain usage of union:

#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> union Data { int i; float f; char str[20]; }; int main( ) { union Data data; data.i = 10; data.f = 220.5; strcpy( data.str, "C Programming"); printf( "data.i : %d\n", data.i); printf( "data.f : %f\n", data.f); printf( "data.str : %s\n", data.str); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

data.i : 1917853763 data.f : 4122360580327794860452759994368.000000 data.str : C Programming

Here we can see that values of i and f members of union got corrupted because final value assigned to the variable has occupied the memory location and this is the reason that the value if str member is getting printed very well. Now let's look into the same example once again where we will use one variable at a time which is the main purpose of having union:

#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> union Data { int i; float f; char str[20]; }; int main( ) { union Data data; data.i = 10; printf( "data.i : %d\n", data.i); data.f = 220.5; printf( "data.f : %f\n", data.f); strcpy( data.str, "C Programming"); printf( "data.str : %s\n", data.str); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

data.i : 10 data.f : 220.500000 data.str : C Programming

Here all the members are getting printed very well because one member is being used at a time.

C - Bit Fields

Suppose your C program contains a number of TRUE/FALSE variables grouped in a structure called status, as follows:

struct { unsigned int widthValidated; unsigned int heightValidated; } status;

This structure requires 8 bytes of memory space but in actual we are going to store either 0 or 1 in each of the variables. The C programming language offers a better way to utilize the memory space in such situation. If you are using such variables inside a structure then you can define the width of a variable which tells the C compiler that you are going to use only those number of bytes. For example above structure can be re-written as follows:

struct { unsigned int widthValidated : 1; unsigned int heightValidated : 1; } status;

Now the above structure will require 4 bytes of memory space for status variable but only 2 bits will be used to store the values. If you will use upto 32 variables each one with a width of 1 bit , then also status structure will use 4 bytes, but as soon as you will have 33 variables then it will allocate next slot of the memory and it will start using 8 bytes. Let us check the following example to understand the concept:

#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> /* define simple structure */ struct { unsigned int widthValidated; unsigned int heightValidated; } status1; /* define a structure with bit fields */ struct { unsigned int widthValidated : 1; unsigned int heightValidated : 1; } status2; int main( ) { printf( "Memory size occupied by status1 : %d\n", sizeof(status1)); printf( "Memory size occupied by status2 : %d\n", sizeof(status2)); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

Memory size occupied by status1 : 8 Memory size occupied by status2 : 4

Bit Field Declaration

The declaration of a bit-field has the form inside a structure:

struct { type [member_name] : width ; };

Below the description of variable elements of a bit field:

| Elements | Description |

|---|---|

| type | An integer type that determines how the bit-field's value is interpreted. The type may be int, signed int, unsigned int. |

| member_name | The name of the bit-field. |

| width | The number of bits in the bit-field. The width must be less than or equal to the bit width of the specified type. |

The variables defined with a predefined width are called bit fields. A bit field can hold more than a single bit for example if you need a variable to store a value from 0 to 7 only then you can define a bit field with a width of 3 bits as follows:

struct { unsigned int age : 3; } Age;

The above structure definition instructs C compiler that age variable is going to use only 3 bits to store the value, if you will try to use more than 3 bits then it will not allow you to do so. Let us try the following example:

#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> struct { unsigned int age : 3; } Age; int main( ) { Age.age = 4; printf( "Sizeof( Age ) : %d\n", sizeof(Age) ); printf( "Age.age : %d\n", Age.age ); Age.age = 7; printf( "Age.age : %d\n", Age.age ); Age.age = 8; printf( "Age.age : %d\n", Age.age ); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled it will compile with warning and when executed, it produces following result:

Sizeof( Age ) : 4 Age.age : 4 Age.age : 7 Age.age : 0

C - typedef

The C programming language provides a keyword called typedef which you can use to give a type a new name. Following is an example to define a term BYTE for one-byte numbers:

typedef unsigned char BYTE;

After this type definitions, the identifier BYTE can be used as an abbreviation for the type unsigned char, for example:.

BYTE b1, b2;

By convention, uppercase letters are used for these definitions to remind the user that the type name is really a symbolic abbreviation, but you can use lowercase, as follows:

typedef unsigned char byte;

You can use typedef to give a name to user defined data type as well. For example you can use typedef with structure to define a new data type and then use that data type to define structure variables directly as follows:

#include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> typedef struct Books { char title[50]; char author[50]; char subject[100]; int book_id; } Book; int main( ) { Book book; strcpy( book.title, "C Programming"); strcpy( book.author, "Nuha Ali"); strcpy( book.subject, "C Programming Tutorial"); book.book_id = 6495407; printf( "Book title : %s\n", book.title); printf( "Book author : %s\n", book.author); printf( "Book subject : %s\n", book.subject); printf( "Book book_id : %d\n", book.book_id); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

Book title : C Programming Book author : Nuha Ali Book subject : C Programming Tutorial Book book_id : 6495407

typedef vs #define

The #define is a C-directive which is also used to define the aliases for various data types similar totypedef but with three differences:

- The typedef is limited to giving symbolic names to types only where as #define can be used to define alias for values as well, like you can define 1 as ONE etc.

- The typedef interpretation is performed by the compiler where as #define statements are processed by the pre-processor.

Following is a simplest usage of #define:

#include <stdio.h> #define TRUE 1 #define FALSE 0 int main( ) { printf( "Value of TRUE : %d\n", TRUE); printf( "Value of FALSE : %d\n", FALSE); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it produces following result:

Value of TRUE : 1 Value of FALSE : 0

C - Input & Output

When we are saying Input that means to feed some data into program. This can be given in the form of file or from command line. C programming language provides a set of built-in functions to read given input and feed it to the program as per requirement.

When we are saying Output that means to display some data on screen, printer or in any file. C programming language provides a set of built-in functions to output the data on the computer screen as well as you can save that data in text or binary files.

The Standard Files

C programming language treats all the devices as files. So devices such as the display are addressed in the same way as files and following three file are automatically opened when a program executes to provide access to the keyboard and screen.

| Standard File | File Pointer | Device |

|---|---|---|

| Standard input | stdin | Keyboard |

| Standard output | stdout | Screen |

| Standard error | stderr | Your screen |

The file points are the means to access the file for reading and writing purpose. This section will explain you how to read values from the screen and how to print the result on the screen.

The getchar() & putchar() functions

The int getchar(void) function reads the next available character from the screen and returns it as an integer. This function reads only single character at a time. You can use this method in the loop in case you want to read more than one characters from the screen.

The int putchar(int c) function puts the passed character on the screen and returns the same character. This function puts only single character at a time. You can use this method in the loop in case you want to display more than one characters on the screen. Check the following example:

#include <stdio.h> int main( ) { int c; printf( "Enter a value :"); c = getchar( ); printf( "\nYou entered: "); putchar( c ); return 0; }

When the above code is compiled and executed, it waits for you to input some text when you enter a text and press enter then program proceeds and reads only a single character and displays it as follows:

$./a.out Enter a value : this is test You entered: t

The gets() & puts() functions

The char *gets(char *s) function reads a line from stdin into the buffer pointed to by s until either a terminating newline or EOF.

The int puts(const char *s) function writes the string s and a trailing newline to stdout.